Follow @guyharloffofficial on Instagram

Guy Harloff, the mystery of the eye

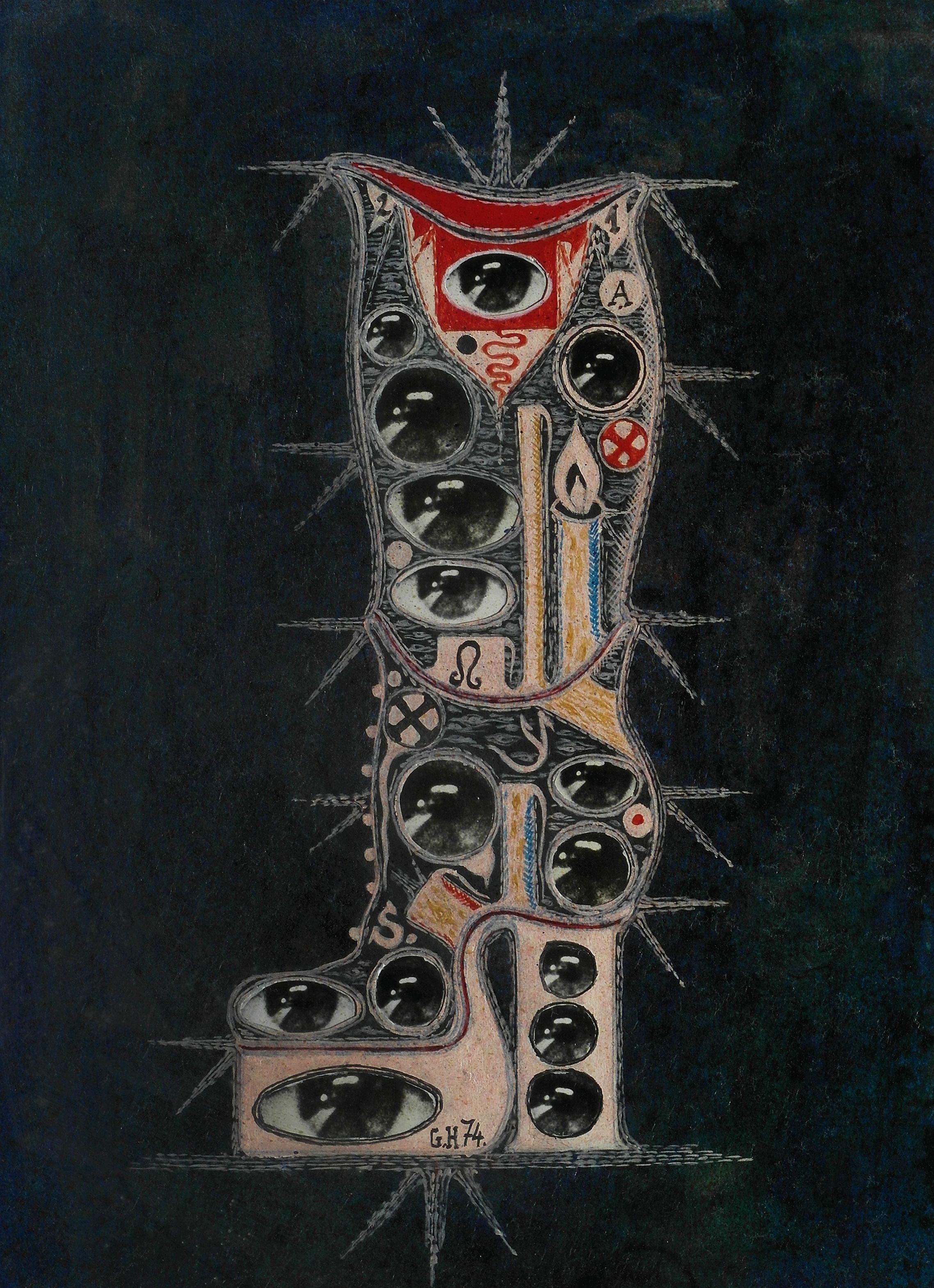

“Symbols are everywhere, they are simply doors that open to other worlds, to other realities.” This was Guy Harloff’s main motto. A sign that persistently returns thoughout his art is the eye, that he considered as the symbol of vision, the ability to see beyond the material dimension, the third eye of extrasensory sight. It is always his right eye (the right eye traditionally symbolizes the creative side of life), which was first drawn and later photographed after 1960, cut out and pasted on the painting surfaces.

The persistent eye symbolism of Harloff’s works was positively affected by the artist’s journey to Iran (1960) and the move to Morocco (1962–1965), that broadened Guy’s creative horizons: he learnt about the secrets of Islamic, Oriental and Arab cultures, and started embellishing his handwriting with a mosaic-like stylization. He developed a life-long interest in Persian miniatures, anthropology, alchemy, Tantra, Sufism and the Jewish Kabbalah. He also developed a vast range of signs in his works, such as pyramids, the mandala, the hand of Fatima, the alchemichal tree of life, the letters of the alphabet, Oriental carpets, the heart, the book, and the wheel – elements inevitably accompanied by annotations, short phrases, and dates to strengthen an awareness of knowledge.

For Harloff, who was deeply influenced by Eastern philosophy, Kabbalah and alchemy, the creation of pictures is therapy: art is incantation. For him, painting became identical with alchemy’s Great Work, in which the refineament of a matter to a noble metal is also an image for the refinement of the person who has travelled the path of kings.

Guy Harloff (Paris, 1933-Galliate, Italy 1991) had a very adventurous life, since in his opinion to refrain was “not good for the soul, nor for the work.” He was a globe-trotter: his father was a very well-known Dutch portait painter of Russian origin, his mother a Swiss of Italian origin; after spending his childhood perpetually moving through Europe with his parents, in 1950 in Rome he landed a job as a second assistant on the set of Vittorio De Sica’s film Termini Station. Cinema remained a great passion of his, especially thanks to the American artist Doris Chase, so much so that in the 1980s he made two films, Petit inventaire and About Life, directed by Arsenije Jovanović. In the early 1950s he briefly approached the Surrealists Breton and Bettencourt, and in 1960 he took part to Europe’s first happening, L’Enterrement de la chose de Tinguely, organized by Jean-Jacques Lebel and Alain Jouffroy. The Surrealist movement and Dada were in fact eye-openers to him. He was also friends with Patrick Waldberg, famous historian of Surrealism, who in 1968 dedicated a monograph to Guy.

His continuos nomadism (he lived in Paris in a studio room in a hotel nicknamed the “Beat Hotel”, toghether with his friends such as Peter Orlowsky, Allen Ginsberg and other Beat Generation artists, in London, at the Chelsea Hotel in New York, in Milan, in Iran, in Morocco, on a boat in Chioggia/Venice, etc.) made him a famous artist and philosopher in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s in France, the United States, and Italy.

He was an international man of culture, and was friends with world-famous artists and intellectuals, such as saxophonist and composer Ornette Coleman (for whom Guy also worked as an agent), artists such as Francis Bacon, Phillip Martin, and Alberto Giacometti, world-renowned art historian Harald Szeeman, who invited him to the great exhibition “Documenta 5” in Kassel and authors such as Alain Jouffroy and Allen Ginsberg.

Guy's intellectual bulimia included cinema, jazz music, philosophy, and was also manifested through the production of cover illustrations for LP records, engravings, ceramics, and seductive small jewelry.

In the works of this modern minaturist, starting from the 1950s to 1990, the viewer can perceive a search for a lost world, reinterpreted in a modern way. For Harloff, we must try to understand what the Orient means to the Western world; once we understand it, we should be able to develop it into our own way of thinking, to find our own path, our knowledge.

Harloff was constantly searching for the philosopher’s stone in art, that great presence composed of restlessness, reflection, and spontaneity.